This blog will be updated throughout the day today

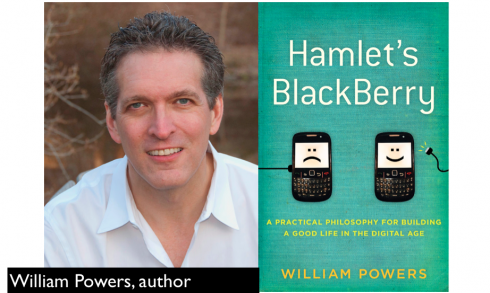

TAKEAWAY: William Powers, author of the soon to be published, Hamlet’s BlackBerry, talks about the effects of digital technology on our forever-connected lives, and takes us on a journey to the ultimate destination: disconnect.

William Powers and I happened to be in New York City at the same time last week, and we agreed to meet at the always cozy and welcoming The M Bar (12 West 44th Street,), conveniently located across from The Harvard Club where William (Harvard ‘83) is staying. I am delighted that William has agreed to a brief interview as we enjoy martinis and bubblies. I know that the conversation will be mostly about the “art of the disconnect”, that rare form of 21st century luxury that seems to elude many as they hold on to every new gadget that the technology has created to connect us better.

William manages to turn “disconnect” into a destination, and his new book, to be published in June, is a sort of travel guide to get us there. I have already given “disconnect” the required three-initial airport code, DCT.

The background

William Powers and I outside the Harvard Club in New York City last week

I came across William Powers at a WAN (World Association of Newspapers) conference in Amsterdam in 2008. I was sitting in the back of the huge conference room, waiting to do a presentation of my own, but I still remember the impact that William’s words had on me.

His keynote presentation was titled “The Eternal Power of Print” and I was impacted by his statement on why paper will endure. “There are cognitive, cultural and social dimensions to the human-paper dynamic that come into play every time any kind of paper, from a tiny Post-it note to a groaning Sunday newspaper, is used to convey, retrieve or store information,” he writes. “Paper does these jobs in a way that pleases us, which is why, for centuries, we have liked having it around. It’s also why we will never give it up as a medium.”

William had written in detail about his belief (and love affair) with print in an academic paper titled “Hamlet’s Blackberry: Why Paper is Eternal,” published by Harvard University’s Joan Shorenstein Center on Press, Politics and Public Policy.

The timing of that paper coincided with a period in our industry when many questioned the durability of print, with obituaries written for daily newspapers in almost every corner of the world. Not that such feeling has disappeared totally, but I think we now have a better sense that print is, indeed, eternal, but that those who publish on paper must adapt to drastic and major changes in how they go about their business. Nonetheless, William is happily surprised about the effect his essay has had:

What I find very telling is the way my essay has taken on a life of its own. Think about it: Who would ever have predicted that a PDF of an academic essay in defense of print media would ever pull in as much attention as that essay has? And in the digital medium! I still hear constantly from people who are discovering the essay for the first time, tweeting about it, assigning it in university courses, etc. There is definitely more to print-on-paper than most futurists want to believe.

The interview

Now, William Powers prepares to take the idea of his Hamlet’s Blackberry paper to a book format. The book, titled Hamlet’s Blackberry: A practical philosophy for building a good life in the digital age (Harper Collins) will appear in June,

Mario: What is the main thrust of your book?

The book is about a yearning that just about everyone has begun to feel in the last few years – to find some space and time away from our BlackBerrys, iPhones and the other screens that now dominate our lives. These devices do wonderful things for us, and I enjoy them as much as anyone. But a couple of years ago, I started to notice that as connectedness become a full-time, around-the-clock condition – I was always within inches of a screen, and constantly checking – it was doing something terrible to my life. I’d become what I call a Digital Maximalist, someone who can’t get away from his screen. I wasn’t the only one. This was around the same time when businesses around the world were realizing that information overload was making their employees less efficient, and hurting the bottom line – by one estimate, overload is now costing the U.S. economy about $1 trillion a year. We’ve gotten so caught up in the upside of connecting, we’ve lost sight of the fact that there’s a downside. It’s time to strike a new balance.

Mario: Ironically, many of the people likely to buy your book, such as myself, are likely to be totally inmersed in the digital world and all its gadgets. What do you have to say to us?

I’m one of those people! Or I was until I realized that to make the most of digital gadgets, you also have to know how to disconnect from them. When we’re always connected, we’re simply not our best selves. We’re less creative, less focused. I argue that in an always-connected world, with the overload and stress it imposes on the mind, life begins to lose its texture and depth. We need to learn how to get back to that wonderful place, Disconnect. Thus, in the coming years I believe that technologies and experiences that offer us some disconnectedness will have a rising value. In a few of the chapters, I discuss ways in which digital technologies could become more like older technologies such as paper, by allowing us to experience content without all the interruptions and distractions we now have to navigate on our screens. The book is written in a very plain-spoken style with lots of examples from everyday life, the goal being to draw in the general reader.

Mario: Let’s talk about the appealing sense of disconnect that you so often refer about it. How do you see paper allowing us to disconnect?

William:

I believe that paper allows us to be alone in a way we’re seldom alone any more. It quiets the mind. And people are hungry for that. True, we all love all these devices, including me and my family. But they’re also driving us crazy. How do you strike a balance between being connected and disconnected? That is what my book is about. I look back at seven moment in history when a new technology came along posing a similar challenge to the one we face now. At each moment I focus on one philosopher who had some useful practical ideas about how to deal with this in everyday life. They range from Plato to Shakespeare to Thoreau. And, of course, I mention Gutenberg. While we always talk about the printing press itself as Gutenberg’s ultimate contribution to civilization, I argue his real achievement was allowing all of us to have the inward experience of reading, that delightful moment of being alone with a page.

Mario: Who do you see as the ideal audience for your book?

William:

Readers of this book will be those who are inmersed in a digital world, but who sense that something is not right; they will be thoughtful people who want to get to the bottom of this conundrum. I think my readers will be those who love books, but who also carry a a BlackBerry or iPad with them.

William tells us that his blog will be up soon at hamletsblackberry.com, where he will be discussing these questions regularly.

Links of interest

– Apple launches 3G iPad, looks to maintain momentum

http://www.reuters.com/article/idUSTRE64002T20100501

– iPad 3G: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly

http://mashable.com/2010/05/02/ipad-3g-review/

– Jobs: Why Apple banned Flash from the iPhone

http://news.cnet.com/8301-30685_3-20003739-264.html?tag=nl.e404

– Microsoft’s Windows Monopoly Now At Risk As Tablet Market Sprouts Without It

http://www.businessinsider.com/microsoft-tablets-2010-4?

– Buyers of E-Books Still Like Print Too, Survey Shows

http://blogs.wsj.com/digits/2010/04/30/buyers-of-e-books-still-like-print-too-survey-shows/