Tom Wolfe 1931-2018

I am sitting in my Florida home in Tampa when the push notification on my Apple Watch brings in the news:

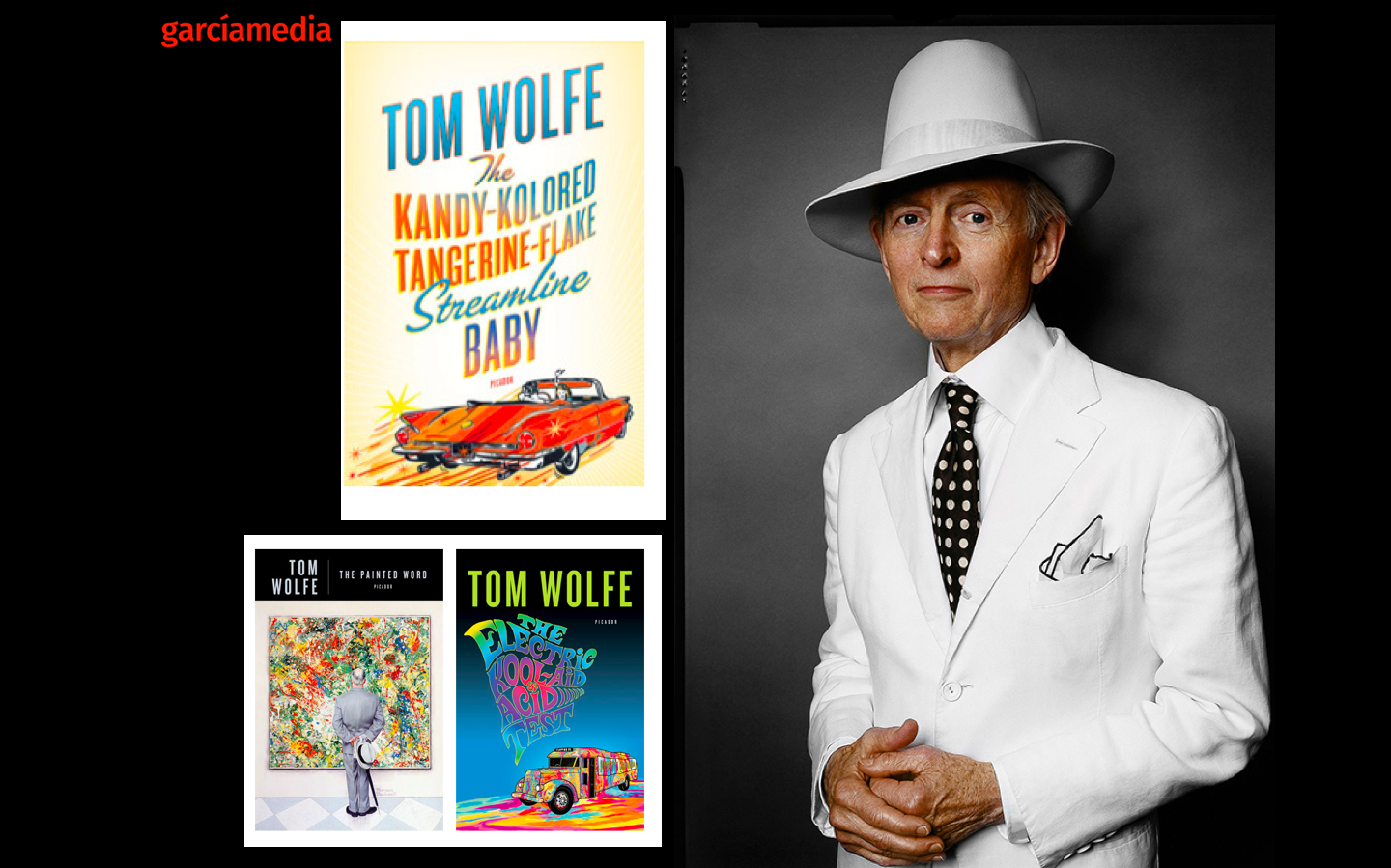

Tom Wolfe, an innovative journalist whose technicolor, wildly punctuated prose brought to life the worlds of California surfers, car customizers, astronauts and Manhattans moneyed status-seekers in works like “The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby,” “The Right Stuff” and “Bonfire of the Vanities,” died on Monday in a Manhattan hospital. He was 87.

Suddenly, I am transported to the summer of 1971, when, as a Newspaper Fund Fellow, I was part of a three-week course at the University of Oklahoma in Norman. One of our professors, Mary Lyle Weeks, introduced us to what was then a new phrase, the New Journalism. Mary Lyle taught feature writing at OU, and she was in charge of preparing us, a group of young high school and college journalism teachers , to learn the latest about writing good features. Mary Lyle was precise, animated and, while not looking at notes, seemed to follow a well outlined presentation in her head. You could tell that she wanted to make sure not one item on her list was left out of her lecture.

It was in one of her first lectures that Mary Lyle went right into the writing of Tom Wolfe and Gay Talese. I confess that I was not aware of those two names.

As a young instructor of journalism at Miami-Dade Community College, my responsibility was to teach Journalism 101: Basic Reporting, while advising the weekly student newspaper, the Falcon Times. As I arrived at the OU workshop, I knew my basic reporting skills, including the 5W’s and the H. With Mary Lyle, and with Prof. Bob Ruggles, who taught us reporting, we learned to expand our reportorial horizons, to emphasize people stories, to evoke emotion through our writing.

The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby

The introduction to Tom Wolfe came via his now iconic piece about the car culture, The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby, originally published in Esquire magazine .

I find the introduction to the piece fascinating even today, because of Wolfe’s reference to typical newspaper features, as in routinely boring:

I went to a Hot Rod & Custom Car show at the Coliseum in New York. Strange afternoon! I was sent up there to cover the Hot Rod & Custom Car show by the New York Herald Tribune, and I brought back exactly the kind of story and of the somnambulistic totem newspapers in America would have come up with. A totem newspaper is the kind people don’t really buy to read but just to have, physically, because they know it supports their own outlook on life.

The words resonate today, in the Trump era, when so many tend to turn to media that supports our own beliefs.

But, back to the The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby. In his introduction Wolfe continues to tell us what he knew his editors expected from his coverage of a car show:

Anyway, I went to the Hot Rod & Custom Car show and wrote a story that would have suited any of the totem newspapers. All the totem newspapers would regard one of these shows as a sideshow, a panopticon, for creeps and kooks; not even wealthy, eccentric creeps and kooks, which would be all right, but lower class creeps and nutballs with dermatitic skin and ratty hair. The totem story usually makes what is known as “gentle fun” of this, which is a way of saying, don’t worry, these people are nothing.

Wolfe wrote such a “routine” or totem story, but he knew he wanted to write a different story:

I knew I had another story all the time, a bona fide story, the real story of the Hot Rod & Custom Car show, but I didn’t know what to do with it. It was outside the system of ideas I was used to working with, even though I had been through the whole Ph.D. route at Yale, in American Studies and everything.

Here were all these . . . weird . . . nutty-looking, crazy baroque custom cars, sitting in little nests of pink angora angel’s hair for the purpose of “glamorous” display—but then I got to talking to one of the men who make them, a fellow named Dale Alexander. He was a very serious and soft-spoken man, about thirty, completely serious about the whole thing, in fact, and pretty soon it became clear, as I talked to this man for a while, that he had been living like the complete artist for years. He had starved, suffered—the whole thing—so he could sit inside a garage and create these cars which more than 99 per cent of the American people would consider ridiculous, vulgar and lower-class-awful beyond comment almost. He had started off with a garage that fixed banged-up cars and everything, to pay the rent, but gradually he couldn’t stand it any more. Creativity—his own custom car art—became an obsession with him. So he became the complete custom car artist. And he said he wasn’t the only one. All the great custom car designers had gone through it. It was the only way. Holy beasts! Starving artists! Inspiration! Only instead of garrets, they had these garages.

Wolfe went to Esquire Magazine with the idea for his story. The editors there liked it and sent Wolfe to California to take a look at the custom car world. An interesting note: while writing the story for Esquire, Wolfe suffered from writer’s block, so he submitted his notes to the editor,Byron Dobel, who simply removed the salutation “Dear Byron” and ran Wolfe’s notes as the article.

That’s how the legendary story came to be. The New Journalism was born.

The New Journalism: a revolution not applauded by all

Suddenly, journalists were contemplating a revolution: the use of novelistic, fictional techniques in nonfiction writing. We who had been trained for total objectivity in our writing, to become invisible as reporters of the story, were exposed to a different genre, where the author took certain liberties with the truth and the more personal features of the story. Not all the journalists of the time approved of the New Journalism, of course.

I remember that, upon returning from my University of Oklahoma workshop, I proposed devoting an entire course to the New Journalism, but the idea did not meet with the approval of my superiors at Miami-Dade. Perhaps it was too new. Maybe it was too daring, so I just simply added a unit on the new style to my reporting classes. Students were fascinated then, as they are now, by this style of journalistic writing, which allowed them to turn their observations of a scene into colorful accounts.

The subjective perspective of the New Journalism, the literary style , the more colorful writing changed our vision of how we could write a story. Suddenly, the leads of even the newsiest stories would contain one sentence, emphasizing an aspect of the story that might contribute to lure us to read the rest. While many consider the New Journalism to have evaporated by the 1980s, I disagree. I think that we see elements of it in multimedia stories, sort of the New Journalism meets linear storytelling, adds videos and audio.

The New Journalism lives in the digital era

Just this week I blogged about two stories that remind me of the style of the New Journalism, one about falling in love in war torn Syria, another one about the rebirth of the city of Detroit.

I can only imagine how The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby would appear today, with a multimedia approach. Yet, as we read Wolfe’s prose, we experience exactly the same sensation as reading the works of Gabriel Garcia Marquez. The writing is so visual, colorful and detailed that nothing else is needed. The imagination is rewarded splendidly with only text on the page.

However, while teaching my Columbia journalism students about linear visual storytelling, I often turn to the work of another exponent of the New Journalism, Gay Talese, and his also iconic story, Frank Sinatra Has a Cold,

I have the students assume that the Talese story was published for the first time today, and how it would be presented on mobile devices.

William F. Buckley, Jr. said of Tom Wolfe :

“He is probably the most skillful writer in America — I mean by that he can do more things with words than anyone else.”

I also remind my students today that it is the people in the story that make it interesting, something we learned from the great Tom Wolfe, too:

“Fortunately, the world is full of people with information compulsion who want to tell you their stories. They want to tell you things that you don’t know. They’re some of the greatest allies that any writer has.”

It is almost the summer of 2018, and Wolfe’s writing and influence are felt just as strongly as when Prof. Mary Lyle Weeks read us passages from his work, exposing us to the New Journalism, and opening doors for us to let our students through. Those doors are still open. It’s still happening.

Thanks, Tom Wolfe. May you rest in peace.

Image: courtesy World Tribune, Getty Images

The NY Times obituary of Tom Wolfe:

All the final Columbia student projects here:

Columbia final projects, Spring 2018

https://www.garciamedia.com/blog/my-columbia-stud…rojects-part-one/

https://www.garciamedia.com/blog/my-columbia-students-final-projects-part-2/

https://www.garciamedia.com/blog/my-columbia-students-final-projects-part-three/

https://www.garciamedia.com/blog/my-columbia-students-final-projects-part-four/

Mario’s Speaking Engagements

June 7-8—WAN-IFRA World Congress, Lisbon, Portugal

For more: http://events.wan-ifra.org/events/70th-world-news-media-congress-25th-world-editors-forum

June 12-14, CUE Days , Aarhus, Denmark

http://www.ccieurope.com/news/6738/Video_What_is_CUE_Days_2018

August 2, Digital House (Facebook workshop), Buenos Aires

October 6, 20, 27–King’s College, New York City

The Basics of Visual Journalism seminars

Garcia Media: Over 25 years at your service

TheMarioBlog post #2839