Lyz Spayd, a former Columbia Journalism School colleague, is now The New York Times' public editor, charged with evaluating journalistic integrity and examining both the quality of the journalism and the standards being applied across the newsroom. She writes a regular column with her observations.

One such column Feb. 5 addressed the issue of copy editing and it made me think that what Liz writes is going to be happening at the Times—primarily fewer eyeballs on stories during the editing process—is something that I am observing in newsrooms across the globe the past two or three years.

In Liz's own words:

THE NEW YORK TIMES has a reputation for impeccable editing. Not just because it can turn one particular story into a showpiece, but because it achieves a high level of consistency and polish across its entire report. It’s part of what readers pay for, and what they’ve come to expect……Soon this conveyor will be replaced by a bespoke editing system built primarily around digital.

I particularly like when Liz uses the words “polish” and “showpiece”, because it is the aim of every writer that his/her piece will be polished and well crafted. More importantly, that the story will be authoritative and credible. When we read publications such as The New York Times, we have come to expect polished showpieces, which we usually get in abundance.

That is why I hope that the Times, as well as newspapers everywhere, will be able to find a comfort zone where the speed of digital journalism can accommodate the essentials of good copy editing. An extra set of eyeballs on a story could make all the difference.

Humanizing the story

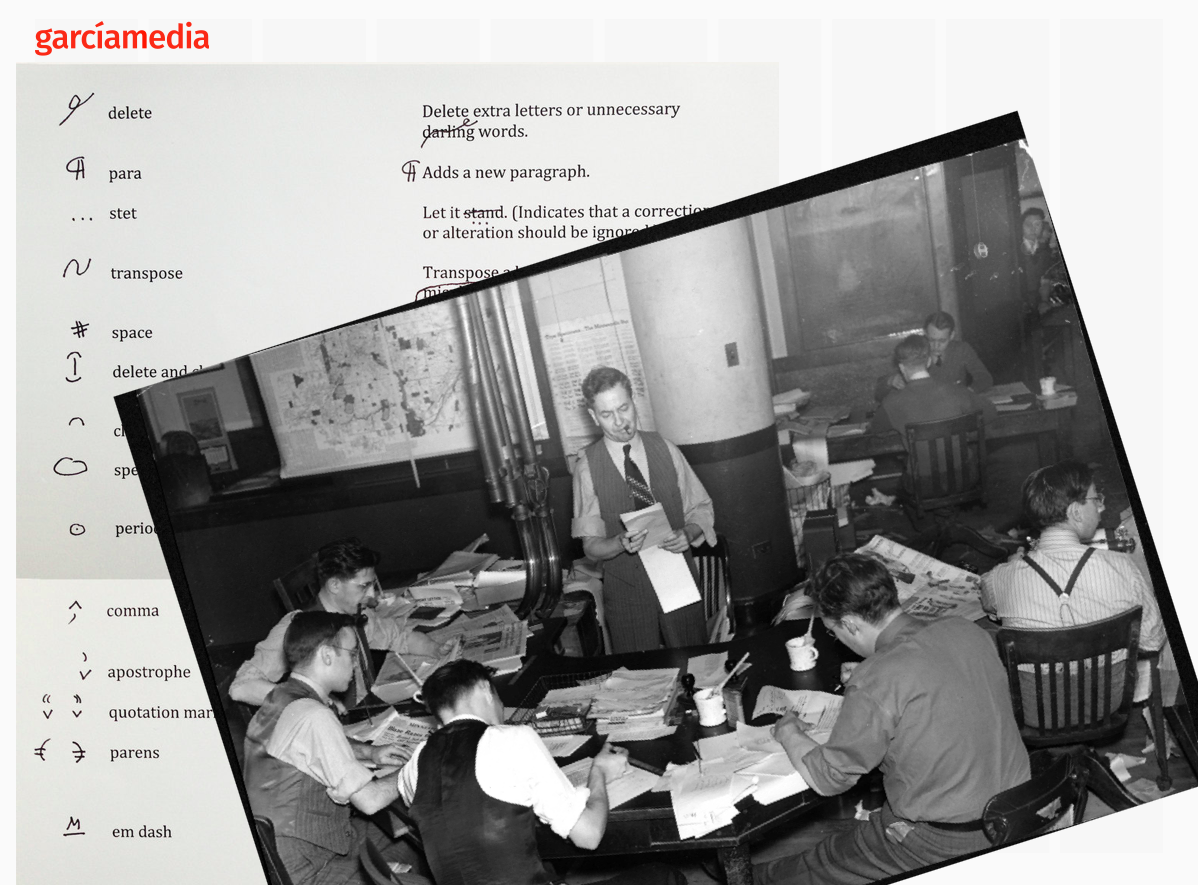

I began my career at The Miami News in 1967 as an intern. I am forever thankful to those copy editors with very sharp grease pencils who taught me much about the structure of stories, the flow of paragraphs, the specific use of certain words, to make a story that could be average and inconsequential read better.

The best copy editors not only polished one's copy, but they questioned it, making us get additional information to help verify facts, or to clarify them for the reader. I remember reporting on a newly opened canning factory in Miami, one of the first larger businesses started by Cubans newly arrived in the City. It was one of those complicated stories on a subject about which I knew very little. I did my homework, conducted interviews with engineers, business execs and workers in the plant, but my story turned out to be too full of numbers and not human enough, according to the copy editor.

“These people are immigrants, they have worked hard to establish themselves here and to start a big business, no less, but your story treats it as if this was the opening of just another new business in Miami. C'mon, get into the hardship, the uphilll battle that these people have gone thru to start a business in the US, then ease into the number of cans that they will fill per minute,” he said.

That's what I needed to change gears, humanize my story and then feel very proud when it appeared, not just another business story but one that had appeal to people not at all interested in the canning of beverages.

I have not forgotten those lessons.

I wish I had a copy editor by my side every morning when I write this blog. It is not practical, but, from time to time, I appeal to friends of mine to read my copy, especially colleague and former USA Today editor, J Ford Huffman, whose pencil is one of the sharpest. Miraculously, we have remained friends even after he has massacred my copy (always to make it better!).

I have recommended to my Columbia students that they read the Liz Spayd piece, and I agree with her that “tearing down one of the industry’s more-heralded editing desks holds inherent risk.”

I am confident that we will be able to accelerate the flow of stories via digital devices but do so while allowing for more than one set of eyes to read the copy.

The art of copy editing must be preserved.