TAKEAWAY: Talking about change is popular in newsrooms globally, welcoming it and implementing it not so. Three possible reasons for editors’ aversion to change. This is Part 1 of 2.

We can welcome change as happily as we do Santa Claus coming down the chimney, or as horribly afraid as facing an impending root canal or an Internal Revenue Service tax audit.

No course we ever take in school ever prepares us to face change. Yet, it is change that we encounter along the way from day one in that first job, internship and when we get into the dynamics of practicing our profession.

Handling change should be a required course, regardless of one’s area of study. In my view, change should become an academic subject, a much needed one.

Every week I face the effect of change in a newsroom somewhere in the world. Every time I am mesmerized by the way some managers in high positions TALK about change, but have trouble accepting it and, of course, implementing it. By the way, I am also impressed by the many who do embrace change with gusto.

The best newsrooms I have experienced, the ones where things move forward, are those where when someone asks “what if?”, someone answers “why not?”.

Change and the newsroom

Why is it so difficult for newspapers, particularly, to adapt change?

I have always maintained that editors are the first to report change in the world around them. One of the best news determinants is that of change: the first man to land in the moon, the first hospital to go totally wireless, the first jumbo jet to offer showers on board. We report all these firsts with bravado.

It is a different story accepting change in our own environment.

In my experience, the three culprits in impeding the way to change in the newsroom are:

It’s not news till it appears in print: Traditional thinking editors who still cling to the notion that it is not really news until it appears in the printed newspaper, until ink touches paper. This has to do, too, with the fact that the great majority of editors in charge trained as print editors. They see their mission as that of protecting print (a worthwhile effort, believe me, but not at the expense of expanding the newer platforms). It is worth noting that only last week The New York Times company reported a profit in the second quarter on stronger circulation revenue and lower operating costs. Digital advertising now accounts for 24.7 percent of the company’s total advertising revenue. It has taken the Times dramatic changes, many of them in the newsroom, to get here.

“The printed paper is still the cash cow”: The fact that in many cases the printed newspaper is still the major source of advertising revenue, prompting publishers and editors to use that as the excuse not to advance with the further development of those much needed digital platforms which, in my view, will be the major sources of revenue in the future. I may add that there is also an element of romancing the printed newspaper that often conspires to keep change at a distance. Romancing the newspaper is totally fine, romancing it to death may not be.

Fear of the unknown: This is probably the most common reason for our aversion to welcome change. I hear it all the time in many of the newsrooms I visit, the fact that many journalists fear to be in the center of that nexus where storytelling meets technology. While a majority of the editors I know are aware that storytelling moves fast and furiously towards those digital platforms—specifically smartphones—they do not know how those platforms work yet, so taking big steps to assimilate them into their operation is not going to happen as quickly as it should.

For these editors, I strongly recommend reflecting on this quote from Steve Jobs, a man who changed the way we consume everything from music to news to social exchanges

For the past 33 years, I have looked in the mirror every morning and asked myself: ‘If today were the last day of my life, would I want to do what I am about to do today?’ And whenever the answer has been ‘No’ for too many days in a row, I know I need to change something.

What works for me

Since we are usually comfortable with what we have, and because it is that level of comfort that makes us more likely to avoid engaging with change, I normally tackle this in my workshops by removing the “comfort” item from the table.

Yes, on day one of a workshop I will ask the question: how would we plan a new publication in this city/country in 2013 if there was NOT an existing one.

Get rid of the history (albeit momentarily).

Get rid of the big elephant in the room (that copy of today’s newspaper as we know it).

Usually, once we get everyone to think in front of a blank page (or screen), elements of change appear.

May not work for all, but it works for me.

Of related interest

40 Years/40 Lessons: Change

https://garciamedia.com/blog/articles/p40_years_40_lessons_26_change._p

Pages we like

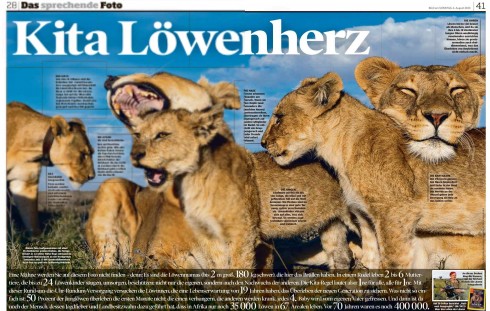

Everything you want to know about lions in this double page from Bild am Sonntag, sent to us by Frank Deville, our European blog correspondent.

Some of the highlights:

-The mama lion can feed up to 24 cubs, including some not her own.

-That mama lion is quite a protector of her cubs: from hunters and even from the babies’ own father.

-The worldwide number of lions has decreased from 400000 to 35000 in the last 70 years.

Tomorrow: How change made an entrance in some of our projects

The Wall Street Journal, Die Zeit, El Tiempo, The Citizen