Update #3, Tuesday, Feb. 9, 02:35 EST

TAKEAWAY: In India, Sakshi turns 2, and like most two year olds, it is growing fast and showing a lot of energy and exhuberance. With close to 9 million readers, and 1.3 million circulation, for Sakshi, covering its local region 100% is the challenge and the goal.

Sakshi is published in Teluga language in the city of Hyderabad, India

Sakshi, that colorful new newspaper that we helped create in Hyderabad, India, in 2008, is now a healthy, active 2-year old. Art director Murali Krishna reports that the circulation for Sakshi is now 1.3 million printed copies, with about 9 million readers.

Sakshi is published in the Teluga language and has positioned itself as the number one newspaper in Andhra Pradesh. For Murali and his team of 250 designers (don’t Indian numbers blow your mind?), the challenge is to design nearly 350 pages every day for the newspaper more than 15 local editions.

For Sakshi, the content formula is simple: tons of local news in the region of Hyderabad, considered to be the second largest market iin India.

I am showing you some of the latest pages received from Murali, showing how this broadsheet emphasizes color, local content and a jazzy look to create its appeal.

Culture and design

Recently, while participating in a design seminar in Europe, a designer in the audience asked me: Don’t you sometimes have to violate your own rules to accommodate very deep rooted local cultural aspects into the design of a publication?

Good question, and I incidentally used Sakshi to support my answer. Seen through the eyes of contemporary design, these pages of the Indian newspaper appear extremely colorful, but such is the ambience in which this newspaper circulates. I went into a store in Hyderabad that sold textiles by the yard. A room was designated as a “bridal selections” area. I took a peek as many young women—-and their mothers—-poured over huge stacks of materials in yellow, purple, red, lilac, pink, orange and lemon hues. A bride is set to wear as many as seven different outfits during the course of an Indian wedding.

Perhaps Sakshi gets married everyday. We knew that yellow would be the color used for the logo, and red would be the color utilized to signal “lead” in that main headline on the page. It may appear chaotic, but there is a color palette at work here; navigation has its place—-and so do the many ads and special offers that are part of what an Indian regional newspaper, in a vernacular language, is expected to serve its readers.

Sakshi’s design would not be suitable even in many Indian markets. Design adapts to the specific needs of the product, its audience, and, of course, its culture.

SAskhi is a good example of that.

Read our case study of Sakshi:

https://garciamedia.com/blog/articles/new_daily_in_telugu_language_for_hyderabad_india

40 Years/40 Lessons

This is part 2 of my occasional series 40 Years/40 Lessons, which I call a “sort of career memoir” capturing highlights and reminiscing about what has been a spectacular journey for me, doing what I love most. Today’s segment: The impact that becoming a refugee has had in my career and my personal life.

Refugee.

Reading the word refugee at the top of this segment, I am sure you are asking a normal question: what does been a refugee have to do with career, which is what this reminiscence is all about?

Everything, I say.

Careers are punctuated by moments in a person’s life, the good and the bad. Besides, in a way, we are all refugees at one time or another, escaping from something, somewhere or someone.

If I had not come to America perhaps my career would have been totally different. Maybe I would have been an actor, instead of a visual journalist. Actually, I was already a child actor, so I would have grown up to continue life as an actor.

Although I don’t consider myself a “refugee” and always disliked that term even when I had just arrived in the US and that was my immigration status, I am aware of the significance that my becoming a refugee continues to have on many of the decisions I make, what I tell my children, how I live my life, my approach to money, and the lessons I learned at the age of 14: don’t attach yourself to anything physical, because it is here today and gone tomorrow. You also learn that nothing is ever as good or as bad as it seems.

This is why I count February 28, 1962 as my second birthday.

A new Mario was forced to be born that day.

I remember that Wednesday distinctly. There are few days of my life that I can recall almost hour by hour, but I do February 28, 1962. I woke up at home in Havana, nervous with anticipation, sad at the prospect of leaving my parents behind and venturing into a new country whose language I did not speak. “It is time to go,” my father told me as he pretended to drink his morning cup of cafe cubano. My mom was unusually silent. Our old cat, Simon, napped on the burgundy sofa, not a care in the world. Cats know, but they pretend a total lack of interest. There are people like that, too. Simon was a fussy ball of yellow hairs that stayed with you long after Simon had jumped off your lap . I transported Simon’s hairs to Miami in my pants that day, along with the three changes of clothing allowed by the Cuban government for those leaving Cuba.

The boy in the blue pin stripe suit

My mother insisted that I travel wearing a pin striped blue suit, freshly ironed white shirt and a tie. “People treat you according to the way you look,” she said. I have not forgotten it to this day. I wondered if a refugee in pin stripes is going to be less of a refugee than the one arriving in a T-shirt. As always, Mama was right. I arrived at Havana’s Rancho Boyeros International Airport and went through the exit procedures. In those days, Castro would grant you 28 days to return to Cuba, or you would not be able to return again. Like me, many children were on the Pan Am flight to Miami, travelling alone, with no parents. At 14, I was one of the oldest. So, because I was wearing a suit and looked respectable, a couple approached me to see if I could “supervise” their children, a boy and girl, ages about 5 and 7, who would meet their aunt in Miami. I did.

My mom was trying not to cry as we said goodbye just before I entered the gate to board the flight to Miami. But she has never been a good actress. I was the professional thespian in the family, a child actor since the age of 8, with roles on television soap operas, commercials and even a secondary role in the film El Joven Rebelde (The Young Rebel) which was about to premiere a few days before I flew to Miami, which is why keeping my departure a secret was a top priority.

The Pan Am prop airplane took off on a beautiful sunny morning. I had a window seat, with the two small children in my care as my travel companions. The little girl tried to compete with me for window space, so we both could look out to the beautiful sea, and the even more beautiful city of Havana that we left behind.

Also left behind, my parents, grandparents, friends, and my acting career.

Peter Pans on the way to a new land

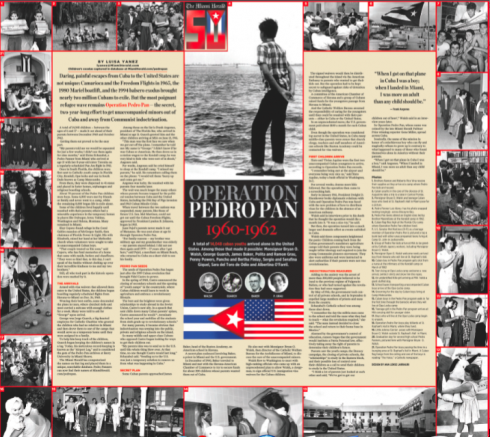

This is a poster designed by Ana Lense Larrauri for The Miami Herald depicting the Peter Pans

It was the beginning of my transformation from child to adult. In exile, all the children who came to the US without their parents between 1960 and 1962 got to be called Peter Pans.

Don’t know why we got stuck with the Peter Pan name. After all, Peter Pan was a boy and Neverland a place for lost boys who never grew up. As for us Cuban Peter Pans, we had to grow up in a hurry. No fairy tale about snapping into attention quickly and adjusting to a life we had no idea existed. On the other hand, for many of us there were fairy tale endings: our parents reunited with us, we grew up Americans, reached the pinnacle of success.

I was a Peter Pan. Most of us Peter Pans are grandparents now. And, although we are in our 50s and 60s chronologically, we are probably more like 80 in terms of maturity. All the Peter Pans flew away from their childhood when they crossed that 90-mile stretch of water between Havana and the US. By the time we saw our parents again, WE were the ones who had already worked in the US and made enough money to welcome our parents with cash available to pay for rental of that first apartment, plus the basic necessities: beds, towels, cooking utensils, and, in the case of Cuban families—-a pressure cooker, a coffee maker and, for my musician father, a saxophone.

Then, we would be the ones speaking for the family, as mom and dad could not speak a word of English. We would deal with banks, door salesmen, school principals and anybody else that the parents needed to communicate with to become official in a new country.

It was a fast track into adulthood. I am happy for that. No regrets.

My first day in America

While my mother probably went back home and cried a little, with Simon the cat on her lap, I had no time for tears.

Here I was in Miami—-that fabulous city by the sea, a mecca for tourists of a certain age, with the tall Miami Beach hotels where names like Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin and Ella Fitzgerald would come regularly to entertain rich guests.

I would be in the care of my uncle Hector and my aunt Matilde. They and their two sons had made Miami their home long before the revolution. My cousins spoke perfect English. They were, for all practical purposes, two American boys. My uncle owned Hector’s Barber Shop, and they lived in a nice two story house with garden and backyard at 381 NW 4th Street, my first US address, which I will never forget.

No sooner had I descended from the Pan Am flight, going thru processing——-my first encounter with a card that described me as a refugee——that I was driven to my uncle’s barber shop. WE hugged, as he stepped from behind the barber chair where he cut the hair of a very tall, blondish man. I remember that the customer was reading a newspaper—-probably The Miami Herald. I saw a sea of type on those two pages. It was the first moment when I said to myself: Hmmmmm, here is a language I can’t read.

I thought of this many years later, in 2003, when I redesigned The Miami Herald.

The meaning of work/study

Next day I was in school, at Ada Merritt Junior High, going from class to class not understanding a word anyone said, but happy to carry all these books in English. I remember the discomfort of physical education class where one had to take off his clothes in front of all the other boys to take a shower before returning to other classes.

My first job was as a bus boy at Suzanne’s Restaurant in Miami—-carrying tray after tray of dirty dishes and glasses at this downtown Miami restaurant where the special of the day at lunch was a mere 99 cents.

Last week I had been an actor in a well viewed soap opera. This week I carried dirty dishes where traces of black or red beans formed surrealistic images which I contemplated in awe.

Who said refugee status and careers don’t mix?

When you are a child refugee your life undergoes a dramatic transformation: your identity papers change, a new language appears, along with new culture and things like root beer (do they drink cough medicine in this country?, I asked my aunt). It is as if someone gives your childhood a double dose of Xanax.

You can’t go home again—-not anymore

On the 28th day of my arrival in Miami, I cried. Going back home to Cuba was no longer a possibility.

My parents had no intention of letting me return plus my visa to return had expired, so here I was, stuck in America, going to class without understanding much, getting naked in front of 30 other boys at precisely 11 am each morning during PE class, and then going to work as a bus boy in a restaurant after school, dressed in white pants, white apron and white hat.

I would take my break at the restaurant about 8 pm, would sit on a wooden crate outside, behind the kitchen, and stare at the moon, which I found to be a good companion those days.

Desperation is when you look up to see if there is someone, or something, out there. Real desperation is thinking that the universe boarded a giant ship and left, but you were forgotten. For my friend Annie——whom I met during my “refugee” days and who remains my best friend today—-desperation relief came from looking up while showering and singing boleros of the time.

However, desperation leads to action: I remember thinking: Mario, time to Americanize, step by step: learn English fast, mingle with your fellow American students, look forward, dream big.

Thinking in English

Learn the language fast———I engaged in conversation often with two ladies in their 70s who lived next to us and who would pay me for me to mow their lawn. These sweet ladies would fix me iced tea to fight the Miami heat in July as I cut the grass in their yards, but they also talked to me non stop and would not laugh at my broken English responses. I would read only in English, and became friends with my American classmates so that I would practice.

Practice I did: I would stand in line at the downtown Miami post office to buy an 8 cent stamp to mail a letter to my parents.

While in line I would repeat to myself a hundred times: “May I have an 8 cent stamp, please?”

Then my turn would come. I would approach the window and give my rehearsed line to the smiling post office employee behind he counter. He, in turn would say:

Anything else I can do for you today? (or something that sounded like that), and I would freeze, totally lost, my best intentions and practice gone for nothing. Had no clue what the man was telling me. I knew my line, but had not prepared for his.

At school, one strict teacher, Mrs. Earle, did not want students to keep their hands on the desk while she talked. Of course, I did not understand her commands.

So, slowly, she moved towards me with a plastic ruler in her hand, then shouted:” Hands off your desk, I said,” and slapped me on both hands with her ruler.

No better way to learn English: I know what “hands off” means. Have never forgotten it.

No, sir, we had no bilingual education available in those days. As a result, we all knew English in 90 days. I still applaud this total immersion method, with no pampering, no catering to one’s special needs. Just the basics. You are here to learn, and YOU are going to learn, damn it.

During episodes like this, sadness would overcome you.

But I remember that something stronger would emerge from the sadness to propel you to try harder. I also learned during this period that life is about the small victories, not so much the big ones.

I felt victorious when I was able to engage my biology classmate, Vera—-a beautiful, fresh faced American girl with deep green eyes—-in a 15 minute conversation, all in English, or when I finished my first English book, Thomas Wolfe’s You Can’t Go Home Again, or when I fully understood my first Emily Dickinson poem.

And, what a sweet little victory: waking up following my first dream totally in English.

No wonder refugee status affects career status. The most successful people I know bask in the little victories, knowing that together they are like beads in a necklace.

Refugee is in my narrative

One reason that the refugee moments shape your career is that others don’t let you forget it.

Let’s face it, we are all in the storytelling business here. We are journalists, and we love a story that involves overcoming unsurmountable odds.

Case in point, and don’t laugh: When I finished my second redesign of The Wall Street Journal,many reporters came to interview me. Half of them had read up on Mario——the good ones always do their homework very thoroughly.

So I particularly remember one woman reporter who asked me:

“Mario, you came to America as a political refugee to escape communism, and now you have been involved with the redesign and rethinking of the ultimate American capitalistic tool. Did you imagine when you came here as a refugee that you would be accomplishing this?”

I have been a reporter, so I know that this is the answer she was desperately hoping for, the one that made for compelling storytelling:

“Yes, of course, it was my purpose, my reason for coming to America. I sat in my Havana living room one day at the age of 12 and said: America, you need me to come and redesign The Wall Street Journal in the years ahead. Get me a visa. Put me on that plane. American capitalism, here I come.”

But, unfortunately, I was not a child prodigy, so this is what I answered the reporter:

“Not really. I knew no English, had no idea what the Wall Street Journal was, and my most important priorities in those days were to count the coins I had collected as tips at the Suzanne Restaurant and put them in a jar, to see how much I could save.”

That I had the opportunity to be chosen to work with The Wall Street Journal, that is a story, but it is not a story about me, it is a story about the country I love, my adopted land, the United States of America, perhaps the only place in the world where a scared little boy, a Cuban refugee, can reach such heights.

That boy in the blue pin stripe suit of 1962 lives inside of me, still searching, still dreaming big, still fascinated by each daily discovery and celebrating the small victories.

At 62, I look at those refugee years with a sense of serene distance, aware that you can’t go home again.

Mario the actor in scenes of The Young Rebel (1961) with fellow actor Blas Mora

For those of you who wish to catch me as Mario the actor, go here: http://cinecuba.blogspot.com/2008/03/el-joven-rebelde-1961.html

1.Mirrors.

https://www.garciamedia.com/blog/articles/40_years_40_lessons_1—a_look_in_the_mirror

TheMarioBlog post #482